The first hundred days of Donald Trump's second presidency have already made history. Not necessarily because of sweeping legislative victories or grand foreign policy realignments, but because for the first time in nearly a century, the American Right has launched a concerted counter-offensive against the administrative state — the so-called "managerial state" born from President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal.

President Trump's Agenda 471, reinforced by the policy blueprints of Project 2025 of the conservative Heritage Foundation and other allied organizations2, appears not to be merely another Republican assault on “big government.” They arguably constitute the first serious attempt at dismantling the entrenched managerial apparatus that has governed the United States for almost a century.

The Managerial Framework

To understand what’s at stake in today’s political battles, it’s useful to revisit James Burnham’s The Managerial Revolution (1941), a work that foresaw the emergence of a new ruling class: the managers. This class was neither made up of capitalists understood in the traditional bourgeois form nor workers in the proletarian form. Instead, it would rise to power through their control of bureaucracies, corporations, and large institutions.

Burnham wrote during a period of profound changes worldwide. The Great Depression had undermined confidence in laissez-faire capitalism, constitutional democracies had begun to appear vulnerable, and authoritarian and totalitarian systems seemed to offer alternatives. Against this backdrop, Burnham argued that capitalism was being replaced by a new system—not socialism, as many expected, but a “managerial society.” In this new order, real power shifted from the owners of capital to those who administered it: executives, government planners, engineers, and bureaucrats.

This transformation cut across ideological lines. Burnham pointed to the New Deal United States, Soviet Russia, and Nazi Germany as different expressions of the same trend. According to Burnham, despite their different political systems and even rivalries, each was increasingly governed by managerial elites who operated the machinery of the state and economy. What united them was not ideology but structure—large-scale, centralized institutions run by professional managers rather than by elected representatives, legislative assemblies, or traditional capitalist owners.

A key insight of Burnham’s analysis was the separation of ownership from control. In classical bourgeois capitalism, those who owned productive assets also controlled them. But in the emerging managerial society, ownership became more dispersed, whether through nationalization or corporate shareholding, while actual control concentrated in the hands of managers. These individuals derived their power not from property rights but from their positions within complex hierarchies.

Burnham saw this as a revolutionary change, akin to the shift from feudalism to capitalism. Power no longer rested with landowners or capitalists but instead with a technocratic class whose authority came from expertise, institutional knowledge, and bureaucratic command.

This framework offers a compelling lens for understanding the rise of the administrative state, the decline of the traditional bourgeois capitalist class in the United States and across the West, and the dominance of institutional decision-makers in both the public and private sectors.

The Birth of the Managerial State and Its Long Shadow

The New Deal fundamentally transformed the relationship between American citizens and the federal government3. Once limited by a strict reading of enumerated powers in the U.S. Constitution, it evolved into a sprawling administrative state capable of regulating nearly every aspect of economic and social life without any constitutional amendment to authorize such changes.

At first, the United States Supreme Court, under a conservative majority adhering to a strict reading of the United States Constitution, struck down large parts of this expansion of federal power. In cases such as Panama Refining Co. v. Ryan (1935), Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States (1935), and Carter v. Carter Coal Co. (1936), the Court invalidated major New Deal programs, including the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) and the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA)4.

The Supreme Court, guided by the Non-Delegation Doctrine5, held that Congress had improperly delegated legislative power to the executive and exceeded its authority under the Commerce Clause. These decisions signaled the conservative-dominated courts commitment to a constitutional order centered on limited federal power and marked the high point of resistance to the emerging managerial revolution.

That resistance soon collapsed in the pivotal case of West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish (1937)6, known as "the switch in time that saved nine," when the Court upheld a state minimum wage law and abandoned the doctrine of "freedom of contract" that had defined the Lochner era7. The shift continued in United States v. Carolene Products Co. (1938), which introduced a tiered approach to judicial scrutiny and signaled that economic regulation would now receive broad judicial deference. Finally, in Wickard v. Filburn (1942), the Court interpreted the Commerce Clause so expansively that all structural limits on federal power were effectively gutted8.

These cases marked a fundamental shift in constitutional interpretation. The Court, now with a majority of jurists sympathetic to New Deal reforms, no longer acted as a check on congressional or executive power in the economic sphere. Congress responded by delegating broad legislative authority to administrative agencies, usually passing laws in general terms while leaving the details to be filled in by technocrats in these agencies. These alphabet soup agencies, like the SEC, FCC, and later the EPA, would acquire the power to enforce their administrative rules and even adjudicate disputes internally.

Judicial doctrines like Chevron Deference from the now overturned Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. (1984)9 later solidified the parameters of these new institutional parameters by requiring courts to uphold agency interpretations of ambiguous statutes. As a result, much of American governance came to be carried out through administrative bodies that have wide latitude of discretion.

All of these developments happened without constitutional amendments. Instead, it was a revolution in constitutional meaning—one that diverged from the text and original structure of the document. In its place, an administrative state arose that many argue operates independently of, and often above, the democratic process and its embodiment in the presidency.

As James Burnham observed in The Managerial Revolution, this legal and institutional transformation paralleled a sociological one: the emergence of a new managerial class that now holds real power through its command of bureaucratic institutions.

An Uneasy Relationship: Republicans and the Bureaucracy

As Republicans gained control of the White House in the post–New Deal era, their relationship with the expanding administrative state was often marked by tension. President Dwight Eisenhower, for example, though a moderate conservative, expressed quiet frustration with what he saw as a self-perpetuating and unaccountable bureaucracy. Echoes of this concern can be heard in his 1961 farewell address, in which he urged vigilance against the growing influence of the so-called Military-Industrial Complex.

The larger conservative tension and unease stemmed from events in the early Cold War, particularly fears of leftist infiltration into key institutions. The case of Alger Hiss, a senior State Department official under FDR who had been a senior advisor to FDR at the Yalta Conference of 1945 and an architect of the United Nations, became a defining moment10. Hiss’s 1948 perjury trial, following accusations of espionage made by former communist Whittaker Chambers, fueled widespread suspicions that New Deal liberals had allowed ideologically suspect figures to infiltrate American government at the highest levels.

Richard Nixon, for example, then a young congressman from California, built his early political career on the Hiss case. The ordeal solidified Nixon’s belief that elite bureaucratic circles were not only insulated from public accountability, but also potentially disloyal to American interests. As president, Nixon planned a major restructuring of the federal bureaucracy during his second term, which is largely forgotten today and set off alarm bells at the time11. These plans were sidelined by the Watergate scandal and Nixon’s resignation from the presidency. In many ways, Nixon’s second-term plans for restructuring the executive branch eerily have parallels with the program currently being pursued by the second Trump administration.

Another episode fueling conservative distrust was the so-called Loss of China12. After the communist victory in the Chinese Civil War in 1949 against nationalist forces, many conservatives blamed State Department officials, especially the China Hands, a group of New Deal-era diplomatic and military officials who had built ties with Mao’s forces during World War II, for what they saw as a catastrophic foreign policy failure. To many on the right, these developments confirmed the perception that America’s foreign policy elite were not simply disinterested experts but ideologically compromised actors advancing a worldview at odds with American values.

Still, Republican presidents who followed, Ronald Reagan and both George Bushes, despite their anti-bureaucratic rhetoric, ultimately governed within the managerial framework. Their reforms were often partial or symbolic, leaving the core structures of the administrative state intact and, in fact, strengthening such structures, as with the Chevron decision, which was handed down during the Reagan administration and was initially seen as a tool for deregulatory efforts. The tension between conservative ideals and the realities of managerial governance remained unresolved, laying the groundwork for future populist backlash.

Trump: The Break and the Offensive

President Trump’s first presidency exposed and amplified a tension that had quietly defined Republican politics for decades: the uneasy relationship between GOP presidents and the administrative state. Under Trump, this long-standing discomfort turned into open confrontation.

The so-called “resistance” within the federal government, consisting of leaks from intelligence agencies, anonymous op-eds by senior officials13, and coordinated pushback from career bureaucrats, brought an unprecedented level of internal conflict. For many on the right, these actions confirmed what they had long suspected: that the federal bureaucracy, far from being a neutral implementer of policy, had become a self-interested political actor hostile to conservative governance.

In response, Trump and his allies began efforts to restructure the executive branch. One of the most consequential was Schedule F14, an executive order issued only a few weeks before the November 2020 elections. This executive order aimed to reclassify tens of thousands of federal workers, potentially up to several hundred thousand, as political appointees. This reclassification would have stripped them of civil service protections and made them subject to presidential oversight and dismissal. Critics condemned the move as a return to the spoils system and warned that it would dismantle the professional civil service established by the Pendleton Act of 188315. Supporters, on the other hand, viewed it as a necessary corrective to a bureaucracy they saw as unaccountable to the electorate.

Although President Biden quickly rescinded Schedule F16, the idea remained central to conservative plans for a second Trump term. Agenda 47 and the Heritage Foundation–backed Project 2025 presented a broad vision for reestablishing full presidential control over the executive branch. These proposals went beyond reshuffling personnel; they sought to dismantle what many conservatives regarded as a fourth branch of government. This branch, in their view, exercises legislative, executive, and judicial powers while remaining largely insulated from democratic pressures.

At the heart of this effort is a deeper constitutional argument: that the modern administrative state represents a departure from the constitutional design intended by the Framers. According to this view, unless the president has direct control over those who enforce the law, democratic accountability becomes an illusion with the being almost relegated to a ceremonial figure sitting on top of a vast structure.

Without Precedent?

While President Trump’s assertive use of executive power in restructuring the federal government may seem unprecedented, and is even called “authoritarian” in some quarters, it has more precedent in American history than many realize. It reflects the use of similar powers by presidents such as Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, and Franklin D. Roosevelt in pursuit of comparable aims.

Among these, President Jackson and his era likely share the most parallels with the current moment in American history, especially in light of the rise of right-wing populism and its fierce opposition to what it sees as an entrenched and corrupt elite.

Jackson redefined the presidential veto, transforming it from what some scholars have argued was originally a safeguard mechanism of corrupt institutions into a political tool turned against those very institutions17. For Jackson, these institutions included those that made up the American System, such as the Second Bank of the United States, internal improvements, and high protective tariffs18.

Jackson exercised executive power most notably to dismantle the Second Bank of the United States. In 1832, he vetoed the Bank’s recharter, declaring it unconstitutional and a threat to individual liberty. He followed this move by withdrawing federal deposits from the Bank19. In doing so, he fired several Treasury secretaries who refused to carry out his orders and redirected the funds to state banks, effectively crippling the institution. The United States would not see another central bank until the passage of the Federal Reserve Act in 1913. In the interim, the country entered a period of so-called free banking, especially in the decades leading up to the Civil War in which the United States came closest to the separation of bank and state.

In his efforts to democratize the federal government, Jackson also introduced the "spoils system," replacing a substantial share of federal officials with political loyalists20. While critics viewed this as patronage, Jackson defended it as a means to bring fresh energy and accountability into government. Today, some on the American Right see this episode as a potential model for a long-term campaign to rein in what they call the managerial state21.

The Jacksonian era, during Jackson’s presidency and that of his immediate successors, arguably marked the true onset of the Industrial Revolution in the United States22. This challenges the common belief that it began only after the Civil War. One interpretation is that Jackson’s restructuring of the federal government—particularly his dismantling of the American System—created institutional conditions that enabled industrial growth, such as moves toward hard money and reductions in tariffs during the 1840s.

Contrary to dismissals of Jacksonians as rabble-rousers, a label also applied to President Trump and his movement, Jacksonians were guided by coherent social, political, and economic ideas that were common across the Anglo-Saxon world of the North Atlantic23. Figures like William M. Gouge, a hard-money advocate and Jacksonian economist whose textbooks remained influential into the early 20th century, drew from British thinkers like Adam Smith and David Ricardo, and engaged in active debates about banking and credit24.

Events on both sides of the Atlantic often mirrored each other. The Jacksonian campaign against the Second Bank of the United States paralleled Britain’s financial reforms under the Peel Act of 1844, which restricted credit issuance. Likewise, Jacksonian tariff reductions in the 1840s coincided with Britain’s repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846. Both moves challenged powerful economic interests.

In this context, President Trump’s push to overhaul the administrative state recalls Jackson’s legacy—an assertive use of executive power to confront entrenched institutions, pursue democratic accountability, and disrupt elite control.

A Pincer Movement

Roughly five years before recent executive efforts to reform the federal bureaucracy, the United States Supreme Court—under its most conservative majority since the 1930s—began steadily chipping away at the legal foundations of the modern administrative state.

The Court’s growing skepticism toward the power of federal agencies has become evident through the rise of the Major Questions Doctrine (MQD). This doctrine has featured prominently in several landmark decisions over the past few years, including West Virginia v. EPA (2022), National Federation of Independent Business v. OSHA (2022), Axon Enterprise, Inc. v. FTC (2023), and Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo (2024)25.

Increasingly, the Supreme Court and the broader federal judiciary are questioning whether Congress can delegate broad and vague powers to administrative agencies, and whether these agencies can act without clear, specific authorization from the legislature26. In the near future, the very legal doctrines that have long shielded the administrative state from direct political control may be significantly weakened—or potentially overturned altogether.

Although the Supreme Court strives to position itself above partisan politics, it remains unavoidably shaped by the political climate. As the elected branches of government grow more antagonistic toward the administrative state, a conservative-dominated Court may feel increasingly confident in developing a more assertive and far-reaching body of case law. Such a trend could challenge the legal framework of administrative law established during the New Deal. One possibility that now seems more viable than in decades past is the revival of the long-dormant Non-Delegation Doctrine, which would sharply curtail Congress’s ability to hand broad rulemaking authority to federal agencies.

Possible Challenges

At the heart of Trump’s counter-revolution is not just the dismantling of institutions perceived as adversarial, but the repurposing of those institutions toward ideological goals through the placement of loyal bureaucrats. This would require a large number of capable and ideologically aligned staff.

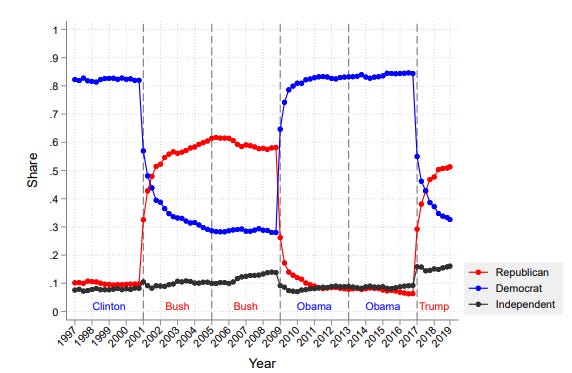

However, despite criticism of over staffing and bloat, the administrative state is staffed with many highly competent professionals. These individuals possess the technical expertise and institutional knowledge necessary to keep the machinery of government running. Replacing them presents a major challenge, particularly because American conservatives has traditionally shown little interest in government careers. Unlike liberals, who often view public service as a natural extension of their political values, conservatives are more likely to gravitate toward the private sector or advocacy roles outside government.

This disconnect has led to a recurring problem for Republican administrations. Historically, they have struggled to quickly and effectively fill the approximately 5,000 political appointee positions available to a president. In contrast, Democratic administrations tend to fill these roles with greater speed and consistency, thanks to a more robust bench of public-sector oriented professionals.

The conservative legal Federalist Society offers a potential solution to this long-term problem. Over the past few decades, it has become the most effective institution in the country at cultivating and networking conservative legal talent27. Its influence on the federal judiciary is proof of its success. A similar model could be extended into other areas of governance such as national security, education, and regulatory policy.

In the short term, Republican leaders may need to rely on co-opting segments of the existing elite—those who are sympathetic to conservative goals or open to collaboration. Such an arrangement can already be seen with the so-called “tech right” but as it such short term arrangements, such has its areas were interest clash. While this is not a long-term fix, it may help bridge the gap while more sustainable networks are being developed.

Without solving this deeper personnel issue, any conservative effort to restructure the federal government will face serious limitations. The counter-revolution will require more than electoral victories. It will require a committed and professional class ready to govern.

Elite Theory and the Inter-Elite Battle

Framed through elite theory, Trump's counter-revolution is not a populist uprising in the purest sense, but rather an inter-elite struggle in which populism serves as a vehicle. One faction of the managerial class, which is ideologically aligned with conservative nationalism and its allies, seeks to displace another faction that is aligned with liberal internationalism and progressivism from control of the state apparatus.

Right-populist figures who preceded Donald Trump's rise, such as Pat Buchanan, recognized early on that defeating the managerial state and its class was essential to achieving their broader goals. Buchanan's early critiques of "bureaucratic liberalism" reflected an understanding that once the machinery of government is captured by a particular ideological class, it can operate largely independent of electoral outcomes.

What Trump represents is the most serious attempt yet to turn these insights into action. His campaign against "deep state" actors and "permanent Washington" is an explicit acknowledgment that winning elections alone is not enough. One must also control the bureaucratic machinery that effectively governs.

The Managerial Revolution: Not a Past Event

James Burnham's The Managerial Revolution was not simply a diagnosis of his time but also a prediction of an ongoing historical process. Burnham foresaw the decline of traditional bourgeois capitalism and the rise of a new ruling class composed of managers, administrators, and technocrats.

Burnham also predicted the shift of global production and power centers, notably recognizing China's potential rise long before it became conventional wisdom. As some commentators have noted, modern-day China might be the best expression of managerialism in the world today, with the leaders of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) coming from highly technical backgrounds that fit the mold of a managerial class.

Today, a core part of Donald Trump's program involves countering the rise of China and the shift in production capacities from Western nations to China. This shift has brought China new wealth and power, altering and continuing to alter global geopolitical dynamics.

Burnham’s framework remains remarkably prescient. The United States' internal political struggles, framed by the so-called culture wars, mirror the broader dynamics he identified: a technocratic class resistant to political challenge, an increasingly globalized economy shifting eastward, and a democratic façade masking an increasingly oligarchic reality.

The counter-revolution we are witnessing may not be the negation of the managerial revolution but rather a new phase within it: a struggle between factions within the managerial elite itself over control of national institutions and the ideological and cultural direction they will enforce, not only on the American state but also on the American nation.

Democracy and the Managerial State

The Managerial Revolution framework also helps illuminate a key paradox at the heart of much contemporary liberalism. Critics of Trump and the populist Right frequently frame their opposition as a defense of "democracy" and warn about the possibility of “democratic backsliding” and authoritarian rule28. Yet in practice, what they often defend is the autonomy of unelected and largely unaccountable bureaucratic structures, precisely the kind of "soft oligarchy" that James Burnham warned would come to characterize modern states.

The tension between the formal mechanisms of democracy—such as elections, representation, and the consent of the governed—and the realities of managerial governance is becoming increasingly difficult to ignore. Managerial elites, operating through regulatory agencies, judicial rulings, and administrative decrees, can wield enormous power insulated from direct electoral accountability. This power permeates from the top into almost all areas of society. In many cases, governance continues unaffected regardless of which political party wins office, reflecting the degree to which the machinery of the state has slipped beyond popular control.

Trump's critics are not wrong to perceive in his movement a profound threat to the established order. But what they too often fail to confront is that a not insignificant segment of the status quo they seek to protect bears only a passing resemblance to the democratic ideal they invoke. Instead of government "by the people," elements of the current setup increasingly resemble government by professionalized elites who claim technical expertise as their source of legitimacy.

Thus, the battle over the administrative state is not simply a contest over policy but over the meaning of democracy itself. Is democracy merely about maintaining constitutional forms while real power resides elsewhere? Or is it about restoring substantive control by the electorate over those who govern in their name?

As these questions become more unavoidable, the legitimacy crisis facing modern liberal democracies is likely to deepen, regardless of whether Trump himself remains the central figure in that conflict.

Conclusion: A New Phase of the Managerial Revolution

In sum, what the past hundred days have revealed may not be the beginning of the end of the managerial revolution, but its evolution into a new and more openly contested phase. Trump’s Agenda 47, Project 2025, and the broader conservative counter-revolution represent the first serious challenge to the managerial state since its birth over 80 years ago.

Whether this counter-revolution succeeds remains an open question. The managerial state, entrenched for nearly a century, will not be easily dislodged. Yet, by mounting a full-spectrum offensive—executive, legislative, judicial, and even ideological—Trump and his allies have ensured that the battle over America's governing structure will define not just this presidency but the political epoch to come.

Burnham understood that history is shaped by the struggles between elites. The managerial counter-revolution of 2025 may prove to be the latest, and perhaps one of the most consequential chapters in that unfolding story, and thus may be the defining elite war of this century.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agenda_47

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Project_2025

https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/united-states-history-primary-source-timeline/great-depression-and-world-war-ii-1929-1945/franklin-delano-roosevelt-and-the-new-deal/

https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/how-fdr-lost-his-brief-war-on-the-supreme-court-2

https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/nondelegation_doctrine

https://mason.gmu.edu/~dcurrie/English_344/Photo_Remix.html

https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/lochner_era#:~:text=The%20Lochner%20era%20ended%20in,Parrish%20.

https://fee.org/articles/wickard-v-filburn-the-supreme-court-case-that-gave-the-federal-government-nearly-unlimited-power/

https://www.ppic.org/blog/unpacking-the-supreme-courts-recent-ruling-on-the-chevron-doctrine/#:~:text=The%20Chevron%20doctrine%20stems%20from,if%20the%20interpretation%20is%20reasonable.

https://www.famous-trials.com/algerhiss/638-home

https://www.nytimes.com/1972/12/30/archives/nixon-counterrevolution.html

https://archive.ph/hUWuA

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/05/opinion/trump-white-house-anonymous-resistance.html

https://brownstone.org/articles/the-astonishing-implications-of-schedule-f/

https://www.americanprogress.org/article/congress-must-pass-the-preventing-a-patronage-system-act-to-protect-federal-civil-servants-impartiality/

https://www.govexec.com/management/2021/01/biden-sign-executive-order-killing-schedule-f-restoring-collective-bargaining-rights/171569/

https://cdn.mises.org/cronyism_liberty_versus_power.pdf

https://thedailyeconomy.org/article/henry-clays-american-system-is-bad-news-for-the-american-economy/

https://billofrightsinstitute.org/essays/andrew-jacksons-veto-of-the-national-bank

https://www.rothbard.it/essays/bureaucracy-and-civil-service.pdf

https://www.theamericanconservative.com/how-to-tame-the-deep-state/

https://opentools.ai/youtube-summary/jacksonian-democracy-and-the-industrialization-of-america

https://books.google.com.na/books?id=UH0HNqRBsmMC&printsec=copyright#v=onepage&q&f=false

“William M. Gouge, Jacksonian Economic Theorist”, by Benjamin G. Rader, Penn State University Press.

https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution-conan/article-2/section-1/clause-1/major-questions-doctrine-and-administrative-agencies

https://www.aei.org/op-eds/the-supreme-court-vs-the-administrative-state/

“How the Federalist Society Won” by Emma Green, published in The New Yorker, August 29, 2022. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/08/29/how-the-federalist-society-won

https://democratic-erosion.org/2025/02/14/erosion-of-democratic-norm-in-trumps-america/

This is too good and very thorough! Whew